Microsoft has re-released its PC Health Check app, but not everyone can use it. Here’s how to use the tool and two third-party alternatives to assess a PC’s ability to upgrade to Windows 11.

In late June, Microsoft announced Windows 11, noted that the upcoming OS would have more stringent hardware requirements than Windows 10, and released a utility named PC Health Check to permit users to assess the upgrade readiness of their PCs. Just four days later, however, Microsoft withdrew the tool from circulation, citing issues with its “level of detail or accuracy.” In other words, it was telling many users that their hardware couldn’t run Windows 11, but it wasn’t telling them why.

To partially make up for the loss of the PC Health Check app, Microsoft published more detailed minimum system requirements for Windows 11, but it also noted that those requirements might change after the company factored in feedback from testers in its Windows Insider program.

As of August 27, the PC Health Check tool is back, and there’s no shortage of third-party options available to those who’d like a report on a PCs’ compliance with — or violation of — the minimum system requirements for Windows 11, which will begin rolling out on October 5. I’ll walk you through the system requirements as they stand now, as well as how to use the PC Health Check app and two alternative tools to check a PC’s Windows 11 upgrade readiness.

Windows 11 system requirements

According to Microsoft’s Windows 11 overview page, the following items delineate the basic requirements a PC must meet for Windows 11 to install properly on that machine. At present, Microsoft has relaxed those restrictions, so that out-of-compliance PCs can run Windows 11 within the Insider Program. But when the official release goes out later this year, those machines will no longer be able to upgrade to newer Windows 11 versions.

- Processor: 64-bit architecture at 1 GHz or faster; Intel: eight-generation or newer (details); AMD Ryzen 3 or better (details); Qualcomm Snapdragon 7c or higher (details)

- RAM: 4 GB or higher

- Storage: 64 GB or larger storage device

- System firmware: UEFI, Secure Boot capable

- TPM: Trusted Platform Module (TPM) version 2.0

- Graphics card: Direct X12 or later capable; WDDM 2.0 driver or newer

- Display: High-def (720p) display, larger than 9” diagonal in size, 8 bits per color channel (or better)

- Internet connection/MSA: Windows 11 Home edition requires internet connectivity and a Microsoft Account (MSA) to complete device setup on first use. Switching out of Windows 11 Home in S mode likewise requires internet connectivity. For all Windows 11 editions, internet access is needed for updates, and to download and use certain features. An MSA is required for some features as well.

Just recently the company also relaxed its CPU restrictions to include certain high-end seventh-generation Intel processors found in some of its Microsoft Surface Studio 2 PCs, as well as certain Xeon processors. (See the details link for Intel in the first list item above.) Otherwise, the limitations stated above are unchanged.

Using Microsoft’s PC Health Check

As I write this story, PC Health Check has been re-released, but it’s currently only available to members of Microsoft’s Windows Insider program. To download PC Health Check, you must be a registered Windows Insider and logged into the associated Microsoft account. Otherwise you’ll get a response from Microsoft Software Download that reads “To access this page, you need to be a member of the Windows Insider program.”

That hurdle overcome, the download is easily accessible as a Microsoft Installer file named WindowsPCHealthCheckSetup.msi. Run this file and the program installs itself.

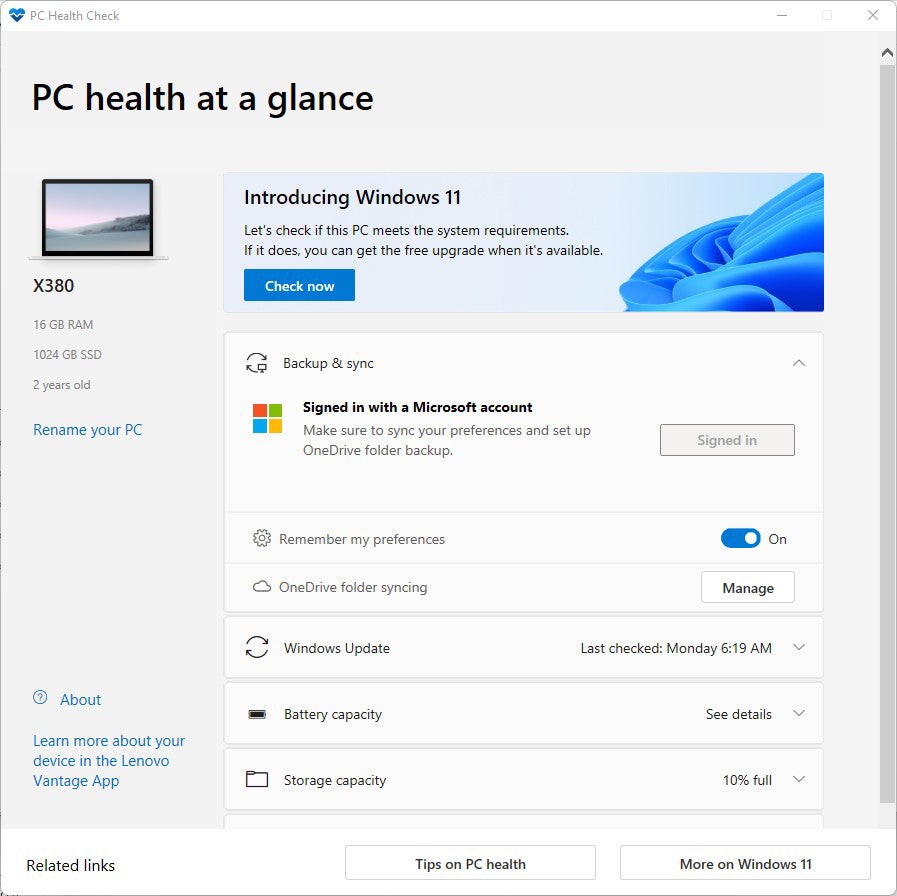

To run the program, type PC Heal into the search box, then run the app from the Start menu. To run its built-in Windows 11 compatibility check, click the Check now button inside the “Introducing Windows 11” pane at the top of the app window, as shown in Figure 1:

IDG

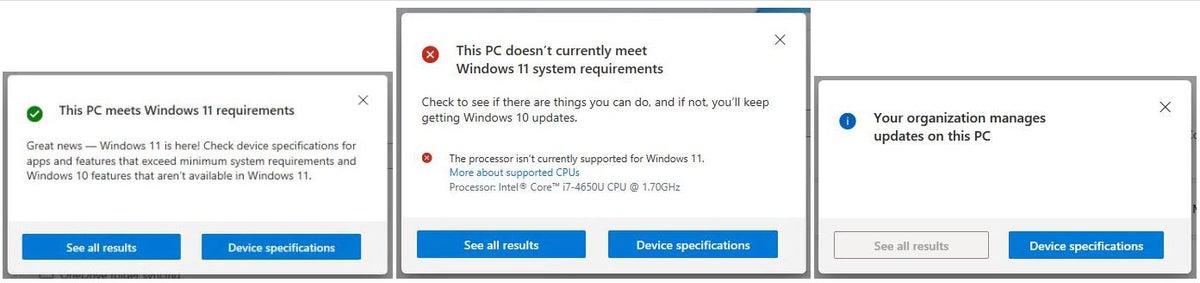

IDGThe program returns one of three possible windows after the compatibility check runs. Those that pass the check get a “meets requirements” message (Figure 2, left); those that fail get a “doesn’t currently meet” message (center); and those from PCs running Windows Education or Enterprise or another Windows version managed by an IT department get a message that reads “Your organization manages updates on this PC” (right) but no compatibility check. I’m running Enterprise on my production PC and have flagged this as an error or problem with Microsoft via its Feedback Hub.

IDG

IDGClick the See all results button to see more details for both passing and failing PCs. The failing PC is a 2014 vintage Surface Pro 3 that fails because its fourth-generation Intel CPU is not supported. The passing grade goes to a 2018 Lenovo ThinkPad X380 Yoga, which has an eighth-generation Intel CPU and other necessary components. Some of the details for both machines appear in Figure 3.

IDG

IDGMicrosoft’s PC Health Check will work for most Windows PCs. Those running Windows 10 Education or Enterprise may be out of luck. Ditto for Windows PCs centrally managed via Group Policy in an organization’s IT environment. YMMV, as they say. And, of course, you might not wish to join the Windows Insider program. That’s why I also recommend the two third-party compatibility check tools in the next section.

Two good alternative Windows 11 compatibility checkers

Though more options are available, I have found two third-party tools to be eminently useful to check a PC for Windows 11 compatibility in enough detail to make them worthwhile:

- WhyNotWin11: a GitHub-based project that runs as a standalone Windows application and reports on a series of checks it performs when run.

- Windows 11 Compatibility Check: a Windows batch file that runs inside an administrative PowerShell session or Command Prompt window to report its findings on PC attributes and capabilities.

Either of these tools can provide you ample intelligence to determine if your PC is ready for Windows 11, with one caveat. Older PCs whose CPUs qualify under the processor requirement may include hardware-based TPM chips of version 1.3 or older (lower in number). These CPUs can emulate TPM 2.0, so what looks like a failure to meet Windows 11 requirements at the hardware level can be offset in software. I will explain further in the section on the Windows 11 Compatibility Check script below.

WhyNotWin11

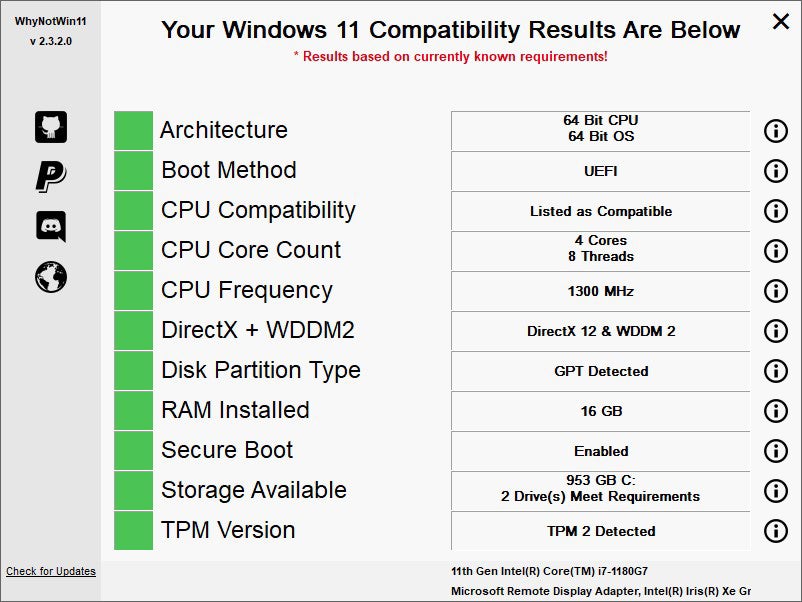

WhyNotWin11 is a GitHub project whose source code is publicly available. The latest release as I write this story is version 2.4.0 (but you can always click the “Latest” button on the home page to jump to the most current vesion). Click the link labeled Download the latest stable release and you’ll end up with a file named WhyNotWin11.exe. By default it resides in the Downloads folder (C:\Users\<username>\Downloads), where you can execute the program directly.

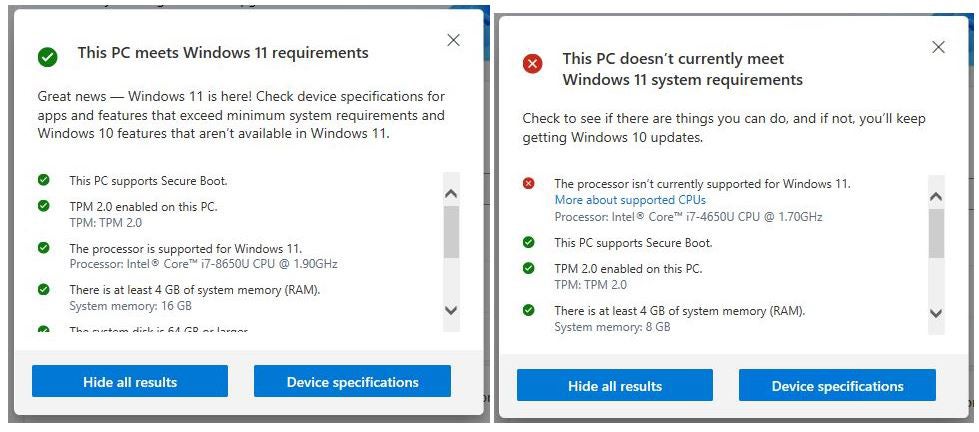

It takes a little while to download the WMIC (Windows Management Instrumentation command-line utility) on which it’s based. When it completes its various checks, it displays their results as shown in Figures 4 (from an incompatible system) and 5 (from a compatible one).

IDG

IDG IDG

IDGUnderstanding WhyNot11’s output is simple: green meets it meets a requirement, red means it doesn’t, and amber means it may or may not meet the final requirements but doesn’t meet current requirements. There’s been a lot of flap about where Microsoft should draw the line on CPU generations, so amber is a sop to those with high hopes for inclusion of older generations. As of the end of August, a few select seventh-generation Intel Core and Xeon processors were allowed into the “meets requirements” group, but no further additions are on the table, according to Microsoft.

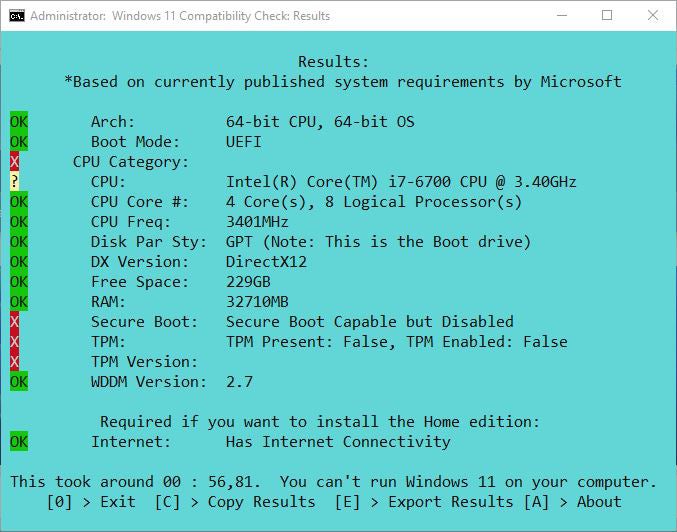

Windows 11 Compatibility Check script

This tool, named Windows 11 Compatibility Check, comes from the community website Windows ElevenForum. Its author, JB Carreon, offers his work as freeware. It comes in the form of a batch file named W11CompChk.bat. Downloads for this tool reside on its History page. As I write this story, the most current version is numbered 1.4.1, for which dates and download links are readily visible.

Once it’s loaded onto your PC, you can simply right-click its entry in File Explorer while holding down the left-hand Shift key on the keyboard. From the resulting pop-up menu, select Copy as path. This copies the full file path into your paste buffer. Next, open an administrative Command Prompt window, paste in the string, and remove the leading and trailing quotation marks (“”).

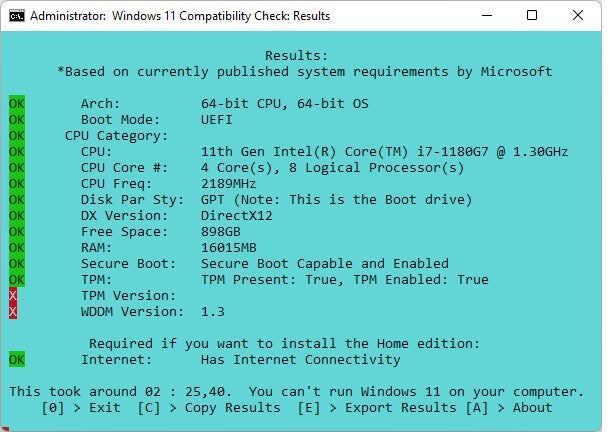

The batch file will then execute. It will show progress, and then a report when it finishes its various checks. Figure 6 shows results from an incompatible PC (the same one as in Figure 4 preceding); Figure 7 shows results from a compatible PC (the same one as in Figure 5).

IDG

IDG IDG

IDGNote in Figure 7 how the Windows 11 Compatibility Check script has been tripped up. While the tool does show that TPM is enabled, it erroneously reports an outdated 1.3 version based on the physical TPM chip present. That chip is emulating TPM 2.0 and therefore does meet the Windows 11 requirements.

Any of these tools will do, but…

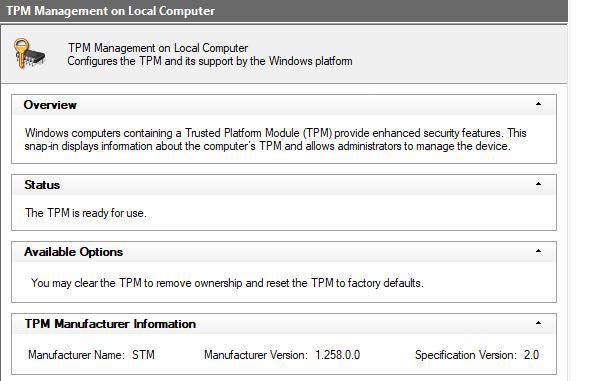

Microsoft’s PC Health Check gets the job done, except for those running Enterprise or Education versions, those whose PCs are under central IT management, or those who are not Windows Insiders. Both it and WhyNotWin11 are smart enough to check which version of TPM is active in the Windows runtime environment. Thus, they correctly identify the TPM as meeting the “version 2.0 or higher” requirement.

If you run the TPM.msc snap-in for the Microsoft Management Console on that PC (you must be logged in with administrative privileges), in fact, it shows you that its “Specification version” is indeed 2.0 (see Figure 8, lower right). That meets the stated requirement and means that the Lenovo X12 ThinkPad in question (built in 2021) will happily and successfully run Windows 11.

IDG

IDGAny tool covered here will help you figure out if (and why) a PC meets or fails the Windows 11 system requirements. I like all three, but I give WhyNotWin11 a slight edge because it gets TPM right and runs on Enterprise, Education, and centrally managed Windows PCs.

This article originally appeared on ComputerWorld.