With SaaS applications the new normal, the humble web browser powers the business world like never before. We take a deep dive into the three leading cross-platform browsers.

What’s the most important piece of productivity software in the business world? Some might say the office suite. But if you look at the time spent actually using software, the answer may well be the web browser. It’s where people do most of their fact-finding and research.

But that’s only a start. These days, web apps like Google Docs, Gmail, Outlook Online, Salesforce, Asana, Jira, and countless others are accessed via the browser as well. So browsers have become your window to work as well as your window to the world.

Which is the best browser for your business? To find out, we’ve put the three leading cross-platform browsers — Google Chrome, Microsoft Edge, and Mozilla Firefox — to the test. We looked at the basics, like overall interface, speed, and HTML compatibility. Then we moved beyond that to safety and privacy, the availability of extensions, syncing data and settings across multiple devices and platforms, and extra features. We ended up comparing the tools each vendor provides for IT to deploy, manage, and configure its browser.

So if you’re looking to switch your company away from its current browser, ready to kick the tires of a different browser, or just plain curious about other options, we’ve got answers for you.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Overall usability

The best browsers don’t get in the way of web browsing, but instead make it easier with straightforward features like managing bookmarks and customizing settings. An ideal browser should fade away so the web itself takes center stage. In this section, we’ll look at each browser’s overall usability, including the interface, bookmark handling, and more.

Chrome

When Chrome was introduced back in 2008, Google took what at the time was a radical, less-is-more approach to browser design: it put websites and their content front and center, stripping out all nonessential browser features. It was the browser equivalent of Google’s stripped-down search interface.

Not much has changed since then. Chrome has held to its austere ethos for all these years, and it’s served the browser well. There’s very little interface visible; it’s pretty much all content.

As for features, all the usual suspects are here: click the + button at the right of your tabs to open a new tab, click the X on any tab to close it, click the star at the far right of the address bar to add it to your bookmarks, and so on. To manage your Google account if you have one, to add another Google account, or to use account-related features such as syncing, click the user icon just to the right of the address bar — the icon is your picture or initial if you’re logged in, or a generic person’s silhouette if not.

And for more settings and features, click the three-dot icon at the far right of the screen to bring up a menu for viewing and managing your bookmarks, viewing your history and downloads, launching a private incognito window, managing your extensions, digging deep into all your settings, and more.

If there’s one drawback to Chrome’s simplicity-is-all-approach, it’s that it doesn’t make it easy to find some of its useful features, like a miniature media controller for playing music and videos (more on that later). To uncover these kinds of features, you’ll have to click around some.

Edge

The new version of Edge, based on the open-source Chromium project launched by Google that also powers Chrome, is everything that the old Edge wasn’t: simple, fast and stripped-down. The old Edge was filled with countless unnecessary features: an e-reader and e-book manager, a way to mark up websites and share the markup with others, and lots of other useless frippery. With Chromium Edge, all that goes away. Microsoft threw in the towel on going its own way with a browser.

The result is a browser with an interface so much like Chrome’s that at a quick glance you might have a hard time telling them apart. Web content takes center stage. Opening and closing tabs works the way you expect it to, and you click the star at the right end of the address bar to add it to your favorites.

IDG

To the right of the address bar are the Favorites manager icon (a star with three horizontal lines); a Collections icon (a + sign over documents or folders), a feature that I’ll cover in more detail in the “Extras” section of this article; and a profile icon (your picture, initial, or a silhouette) — click it to manage your Microsoft account in the same way Chrome lets you manage your Google account. The three-dot icon on the far right launches a menu for viewing your history and downloads, managing your extensions, launching a new private browsing window, adjusting your settings, and so on.

Firefox

Firefox isn’t based on Chromium as are Chrome and Edge, but like those two browsers, it has shrunk down the interface to make more room for web content. Tab handling follows the usual conventions. So does adding bookmarks. And as with the other two browsers, a series of icons to the right of the address bar give you access to other features.

That’s where the difference between Firefox and the other two browsers comes in. Firefox offers more features than the other two browsers via these icons. If you’re content to ignore them, that’ll make no difference to the ease of web browsing. But if you decide to click them, you might get a bit confused.

IDG

The far right area of the address bar is a bit cluttered, with three different icons. The leftmost, three horizontal dots, brings up a menu for bookmarking the page, copying its link, emailing its link, sending the tab to another device, taking a screenshot, and other actions. The one next to it, an icon of a shield, lets you save the page to an app called Pocket, which lets you later view all the content on a variety of devices. (More on that feature later in the story.) The far-right one, a star, lets you bookmark the page and manage bookmarks.

Then to the right of the address bar are four more icons, a “library” icon for managing bookmarks, history, downloads and more; a book icon for opening a bookmarks sidebar; a person icon for managing your Firefox account; and a “hamburger” menu icon (three horizontal lines) for a variety of features such as launching a private window, getting access to settings, managing add-ons and more.

It’s all somewhat of a confusing hodge-podge. Firefox would do well to simplify its interface.

The best browsers for overall usability

Chrome and Edge, based on the same Chromium code, are streamlined, simple, easy-to-use browsers. Those who care about a clean, simple interface will favor them over Firefox.

Speed, system resource use, and HTML compatibility

No matter how many bells and whistles a browser has, and no matter how elegant or useful the design, if it’s slow or hogs your system resources you won’t want to use it. And if it doesn’t adhere to web standards you don’t want to use it, either.

So I put Chrome, Edge, and Firefox through a series of tests to see how each performs in speed, system resource usage, and HTML compatibility. For all the tests, I used a clean, just-launched version of each browser free of extensions, running on the same Windows PC. I didn’t sign into any websites. I ran each test three times and averaged the results.

Speed tests

To test speed of loading pages, browsing, and using web apps, I chose three tests.

- JetStream 2 is a JavaScript and WebAssembly suite that tests how browsers react to advanced web applications. According to its website, “It rewards browsers that start up quickly, execute code quickly, and run smoothly.”

- WebXPRT 3 uses HTML5- and JavaScript-based scenarios to test browser performance, including for photo editing, organizing photos using artificial intelligence, calculating stock option prices, encrypting notes, scanning with OCR, creating graphs, and doing homework online.

- Speedometer 2.0 measures how responsive browsers are overall to running web applications.

For all three tests, the higher the number, the better the browser performance.

The results? A mixed bag. Chrome performed the best in the JetStream 2 test, scoring 107.383, with Edge barely behind at 102.786 and Firefox trailing well behind at 78.47. Edge led the pack in the Speedometer 2.0 test with a score of 93.4 to Chrome’s 90.2, while Firefox scored a lowly 69.6. However, Firefox handily beat the others in the WebXPRT 3 test, scoring 196 to Chrome’s 166 and Edge’s 163.

What does all this mean in the real world? Perhaps not much. I didn’t notice any practical difference among the three during the course of my normal web browsing. However, given the wide variance in performance results, it’s possible that one browser might be speedier than the others in one website or app but not another. So if performance is absolutely necessary for you for a particular website, I recommend you try all three on that one site, and make your decision based on that.

RAM and CPU tests

I also tested how much RAM and CPU each browser used by loading ten websites into different tabs, waiting a minute, then using Windows Task Manager to measure the system resources each browser used. In these tests, lower numbers are better.

Here Edge topped the other browsers. It used 1.275GB of RAM and 5% CPU usage, followed by Chrome with 1.428GB RAM and 7.3% CPU use. Firefox came in last with 1.917GB RAM and 8.4% CPU use. So if you’re multitasking using many different applications in addition to your browser, you may well notice a slowdown in Firefox versus the other two browsers. And in those situations, you’d likely do best using Edge.

HTML tests

Finally, to test HTML compatibility, I used what is generally accepted as the gold standard of HTML testing, html5test.com.

Edge and Chrome were tied in this test, each scoring 528 out of a possible 555 and supporting the exact same web standards. Firefox was a bit behind them at 511. Firefox scored lower because it lacks support for some features including Dolby audio and speech recognition. It lost most of its points for not supporting a variety of forms features, scoring only 52 out of 65 possible points on that section of the test, while Edge and Chrome scored 64 out of 65.

The best browser for speed, system resource use, and HTML compatibility

Edge ekes out a slight victory over Chrome here. Edge and Chrome clock close to identically in the various speed tests and scored the same on the HTML test. But in my tests, Edge used less system resources. Firefox trails the other two browsers in two of the three speed tests, RAM and CPU use, and HTML compatibility.

Safety and privacy

The web isn’t a safe place. There’s malware out there, drive-by-download sites, and plenty of sites that are just plain up to no good. And that’s not all. Even the trustworthy sites may be tracking your online activity and sharing it with others without your knowledge or consent. So we compared how the browsers stack up for security and privacy.

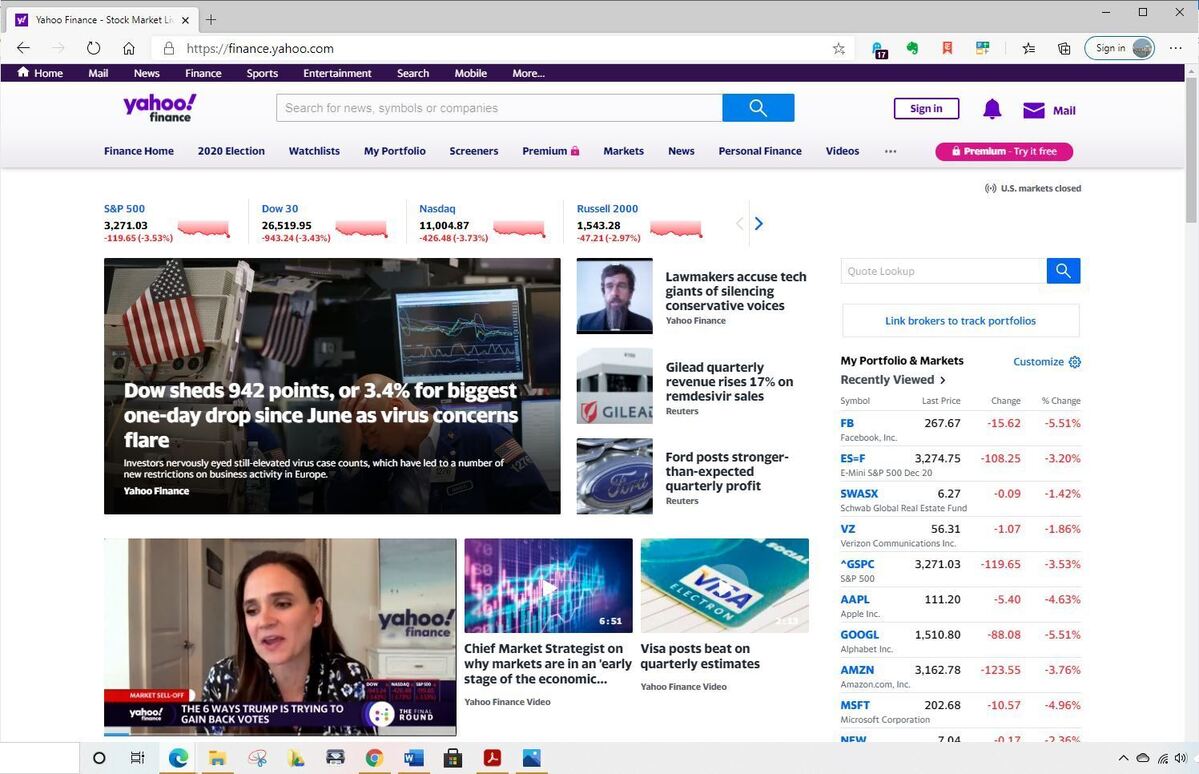

Chrome

Chrome has most of the safety and privacy features and settings you’d expect in a browser, including stopping malware and drive-by downloads and the ability to limit or stop cookies being placed on your PC. (Its Incognito mode, like similar features in other browsers, lets you turn off browsing history on your local computer but doesn’t actually allow you to browse the web anonymously, as is widely believed.) You get to them all in the “Privacy and security” section of Settings.

Here you can customize your settings by controlling websites’ ability to access your camera or microphone, for example, or by blocking third-party cookies. Third-party cookies are those put on your computer by a site other than the one you’re currently visiting. They’re typically used to track your behavior across sites. Chrome also lets you send a “Do Not Track” request to websites. However, while that may sound useful, it’s not particularly effective, because websites don’t have to adhere to your request.

Chrome does, though, have a “Safety check” feature that examines your browser settings for possible privacy and safety holes, and looks for potentially harmful extensions and possible compromised passwords. It warns you if it finds any issues and makes recommendations about how to fix them.

However, in practice it can be problematic. It found four saved passwords on my machine that it said had been compromised. But when I went to the screen that supposedly listed my four compromised passwords, there were 165 there. In addition, merely changing those passwords in my browser won’t change it on the sites themselves. So the utility of the password-checking feature, at least, leaves plenty to be desired.

IDG

Computerworld’s in-depth comparison of the leading desktop browsers’ built-in privacy capabilities ranks Chrome behind Edge and Firefox in privacy controls. Chrome doesn’t let you prevent cross-site tracking, block trackers, or control video auto-play (sound, however, is auto-muted). On the plus side, it does allow you to use a secure DNS provider.

Edge

Like Chrome, Edge stops malware and drive-by downloads, and it lets you limit or stop cookies being placed on your PC; control the default behavior when websites request access to your camera, microphone, location; allow you to use a secure DNS provider; and so on. It also has an incognito mode called InPrivate that disables browsing history on your local computer only, and it will send a “Do Not Track” request, although as I’ve explained, its usefulness is suspect.

Most notable about Edge’s privacy protections is tracking prevention, which blocks ad providers from tracking you from website to website. That makes it more difficult for companies like Google, Facebook, and others to build comprehensive profiles of your activities and interests.

IDG

By default, tracking prevention is turned on. But you can customize how it works, making it less or more restrictive depending on how much privacy you would like when browsing the web and how much you want to see ads and content that mirror your interests. To do it, click the three-dot icon at the top right of Edge’s screen and select Settings > Privacy, Search, and Services.

You have three tracking prevention choices:

- Basic allows most trackers and blocks only those that Microsoft considers harmful. You’ll have less privacy but will be more likely to see personalized ads and content.

- Balanced is the default setting; it blocks more trackers than the Basic setting. Ads and content won’t be as personalized, but sites should still work properly.

- Strict blocks the majority of trackers from all websites, as well as harmful ads. This gives you the most privacy, and ads and content will have minimal personalization. Parts of websites may not work properly when you choose this setting.

You can customize tracking prevention further by clicking Exceptions. That will let you specify sites on which you’d like to allow all trackers. Edge also allows you to see which ad trackers it has blocked. Click Blocked trackers to see them.

You can also see which trackers have been blocked on any website you’re currently visiting and fine-tune your protection on a site-by-site basis. To do it, click the lock icon to the left of the URL in the address bar, and you’ll see information such as the number of cookies put on your device by the site, trackers blocked and so on. Click the cookies icon to see each individual cookie. You’ll also be able to remove any cookies and block any others the next time you visit the site.

However, Microsoft also uses Edge to collect diagnostic data to, in the words of Microsoft, “keep Microsoft Edge secure, up to date and performing as expected.” That worries some people, while for others, it’s no problem at all. So you’ll have to decide whether it’s worrisome. You can control what data Edge gathers and eliminate some of it. For details, see Microsoft’s “Microsoft Edge, browsing data, and privacy” support page.

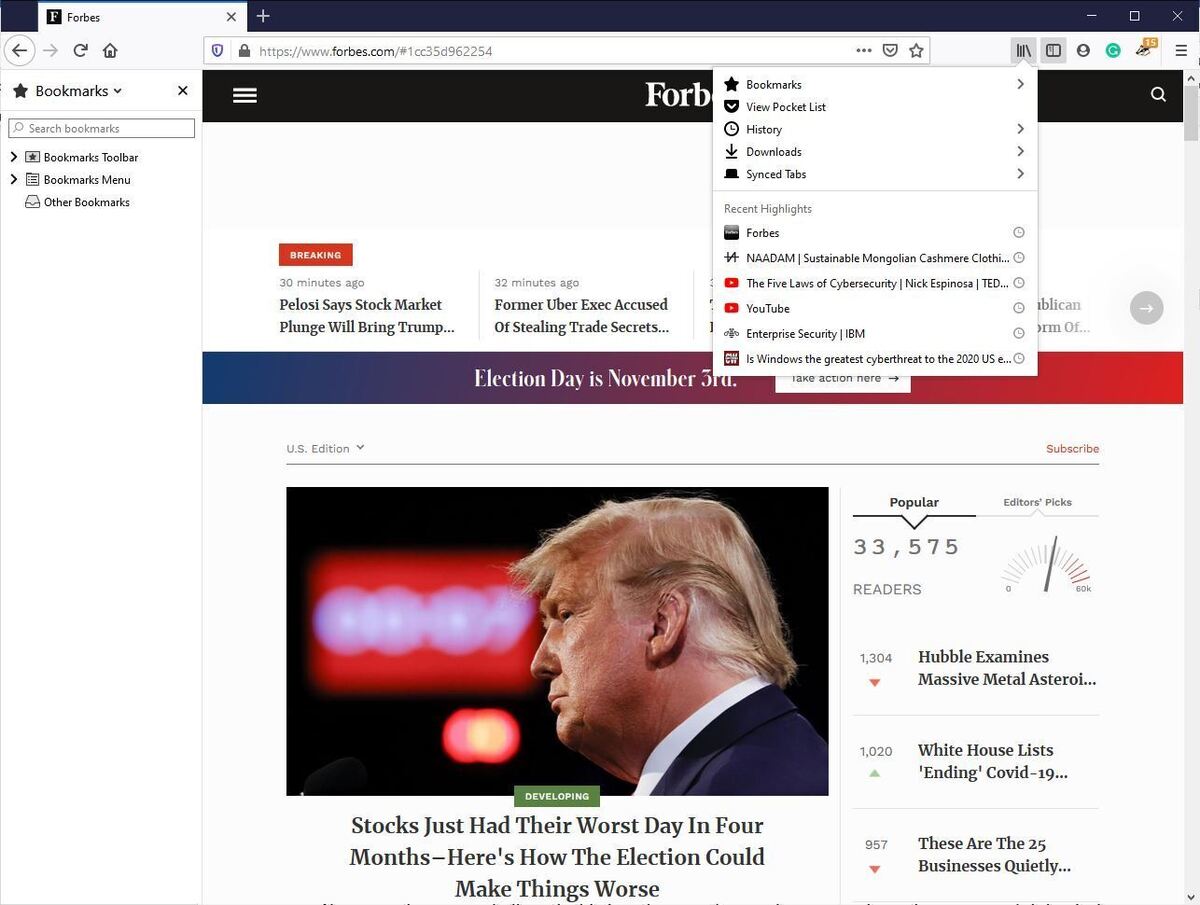

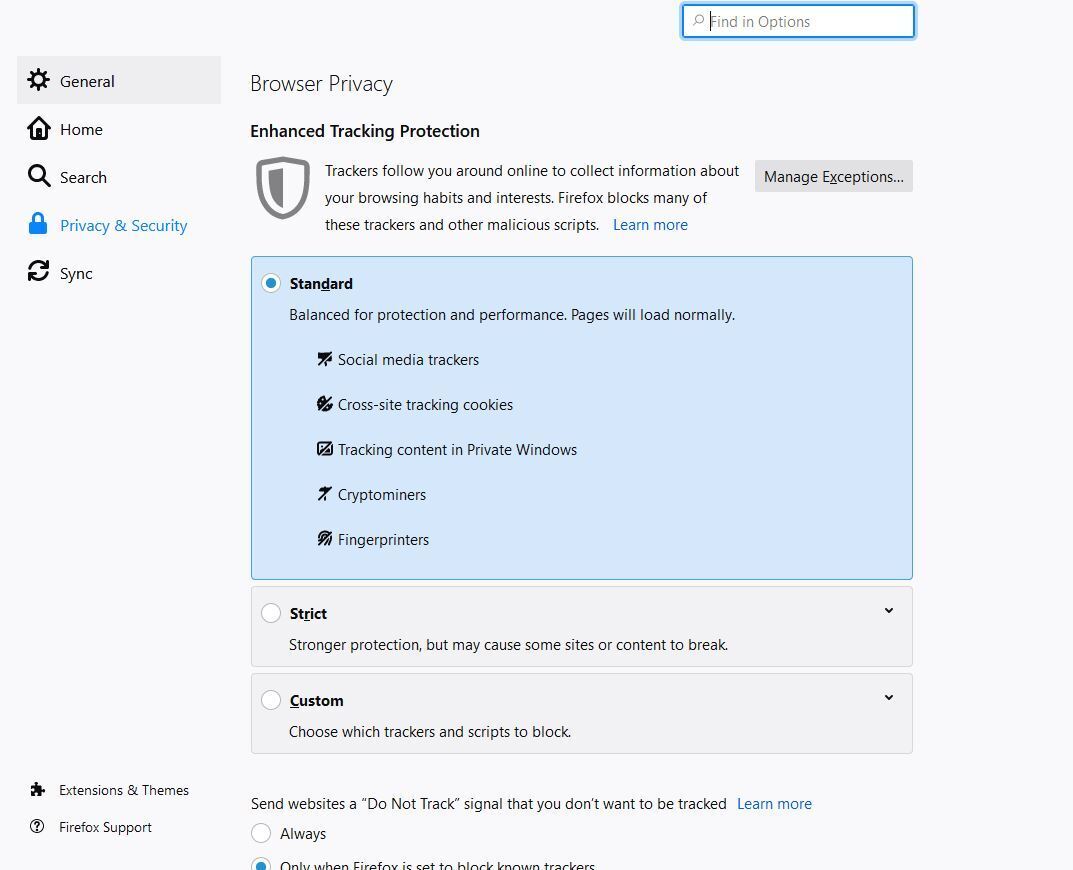

Firefox

No surprise: Firefox starts with the same basic security and privacy protections as Edge and Chrome, including killing malware and drive-by downloads as well as the ability to limit or stop cookies being placed on your PC and control access to your camera, microphone, and location data. On the downside, Firefox doesn’t let you use a secure DNS provider, which the other two browsers do.

Like both Edge and Chrome, Firefox has an incognito mode called Private Browsing that disables browsing history locally on your computer, and it can send a “Do Not Track” signal to websites, for what it’s worth — which generally is not much.

It also offers what it calls Enhanced Tracking Protection, similar to Edge’s tracking prevention feature. It halts social media trackers, cross-site tracking cookies, and cryptominers (software that hijacks a PC to run code that creates cryptocurrency like Bitcoin). Mozilla says Firefox can also prevent browser fingerprinting, a technique that can uniquely identify and track your browser, but testing with the EFF’s Panopticlick privacy analysis tool reveals that it doesn’t.

Firefox offers three levels of tracking protection:

- Standard, the default, is balanced for protection and performance.

- Strict offers stronger protection but can break some websites or block some content.

- Custom lets you pick and choose which trackers and scripts to block.

IDG

As with Edge’s tracking prevention feature, you can watch Enhanced Tracking Protection in action. Click the shield icon to the left of the URL in the address bar, and you’ll get a summary of what the feature did on that site — for example, that it stopped a social network from tracking you on the site, that it didn’t come across any cryptominers, and similar information. You can turn off Enhanced Tracking Protection from that screen as well.

Firefox also has a useful Protections Dashboard that shows you your protection level and data about what protection you’ve received from it, including the total number of trackers blocked on a daily and weekly basis, by category. To get to it, click the hamburger menu icon in the upper-right corner of the screen and choose Protections Dashboard.

From here you can also sign up for data breach alerts, which informs you of any breaches that have included your email address. For each breach you’re told about your potential compromised data, such as passwords, email addresses, IP address, and phone number. And it offers advice for each breach about how to protect yourself from it, including changing your password, updating other logins with the same password, and using a password manager. Unsurprisingly, it recommends you download and use the Firefox Lockwise password manager to do that.

The best browser for safety and privacy

Each browser offers the same basic protections, and so their defaults work quite well in keeping you safe and giving you the tools to try and protect your privacy. Edge and Firefox go beyond that with their blocking of trackers and related technologies, and the ability to customize how each works. Firefox gets the nod here over Edge because of its useful Protection Dashboard, particularly the feature that warns you if your email address has been involved in a data breach and offers advice on how to resolve it.

Extensions

A browser by itself is certainly useful, but it can be powered up and customized by extensions. These browser add-ons can do an almost mind-boggling number of things. Want to block ads, use a secure password manager, edit graphics, read PDF files, handle your mail better, or do thousands of other things? Then extensions are for you.

In this section we look at how rich each browser’s add-on ecosystem is, and how easy it is to install, use, manage, and uninstall them.

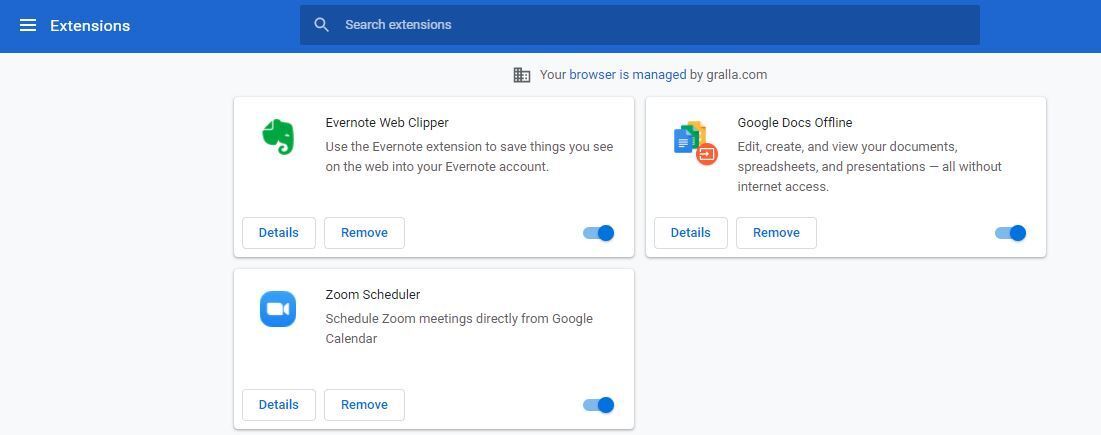

Chrome

Chrome’s rise to become the most popular browser in the world was fueled in part by its support for extensions and the vast number of add-ons available for it. There’s no definitive answer for the total number, although one analysis put it at more than 137,000 as of June 2020.

More important than the total number, though, is whether they’re useful. And by any measure, Chrome extensions are exceedingly useful. You typically install them via the Chrome Web Store, although you can also install them directly from a website. But take care that the site is a reputable one. Google does work to make sure the extensions in its store are free of malware, so whenever you install one outside that store, you may be taking a chance.

To install from the Chrome Web Store, when you’re reading a description of an extension, click the Add to Chrome button on the upper right of the screen. You’ll get a notification about the access it will have to your PC, for example, “Read and change all your data on the websites you visit” or “Display notifications.” If you decide to go ahead, click Add extension. After a short time, the extension will install, and you’ll see its icon on the upper right of the screen. Click the icon to use it and to change any of its settings.

When you’ve installed more than one extension, instead of seeing icons for each separate extension, you’ll see a single icon of a puzzle piece. Click it to get access to all your extensions, to use their features, change their options and remove them from Chrome. From here you can also choose to pin icons for individual extensions to the top right of Chrome, next to the puzzle piece icon.

You can also manage and remove them by clicking the puzzle piece icon and selecting Manage Extensions or by clicking the vertical three-dot menu at the top of Chrome and selecting More Tools > Extensions. This takes you to the Extensions page, where you can find more details about any extension, adjust its settings, remove it, or disable it — which turns it off while still keeping it installed. That way, you can easily re-enable it without having to reinstall it.

IDG

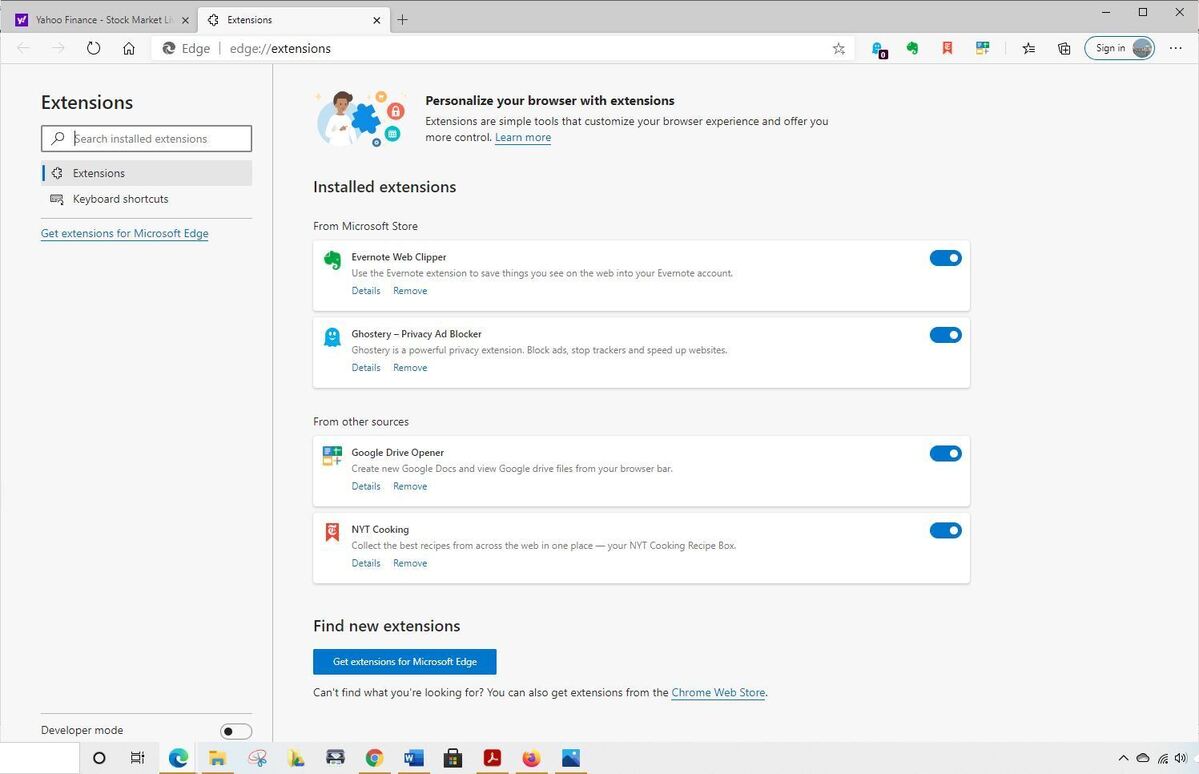

Edge

In the pre-Chromium days of Edge, one of the browser’s many problems was how few extensions it had. By the time the new Chromium version of Edge was released, the old version had fewer than 300 extensions, not tens of thousands like Chrome and Firefox. The extension store for the old version of Edge has only about 265 of them as I write this.

With the move to Chromium, all that has changed. That’s because Edge can now use extensions built for Chrome. When the Chromium-based version of Edge was released, Microsoft warned people that some Chrome extensions might not work on Edge, notably those that rely on Google account functionality to sign in or sync data or those that rely on companion software on your PC. However, I’ve been using the Chromium version of Edge since its introduction in mid-January of 2020 and haven’t come across a single one that didn’t work, including multiple add-ons that require signing into a Google account.

Microsoft has an extension store for the Chromium version of Edge. Get to it by clicking the three-dot icon at the top right of Edge, selecting Extensions and clicking Get extensions for Microsoft Edge. The Edge Add-ons store doesn’t have nearly as many extensions as the Chrome Web Store. But that’s no problem, because you can also install extensions into Edge directly from the Chrome Web Store.

Go to the Chrome Web Store and select Allow extensions from other stores on the banner at the top of the screen. If that banner doesn’t appear and you can’t download extensions, you can click the three-dot icon at the top right of Edge, select Extensions and move the slider from off to on next to Allow extensions from other stores at the bottom left of the screen.

Unlike Chrome, Edge shows each extension’s icon at the top right of the screen. As with Chrome, click any add-on’s icon to manage, uninstall or select what features you want to use. You can also manage and remove them by clicking the three-dot icon at the top right of Edge and selecting Extensions. As with Chrome, from here you can disable and enable extensions as well.

IDG

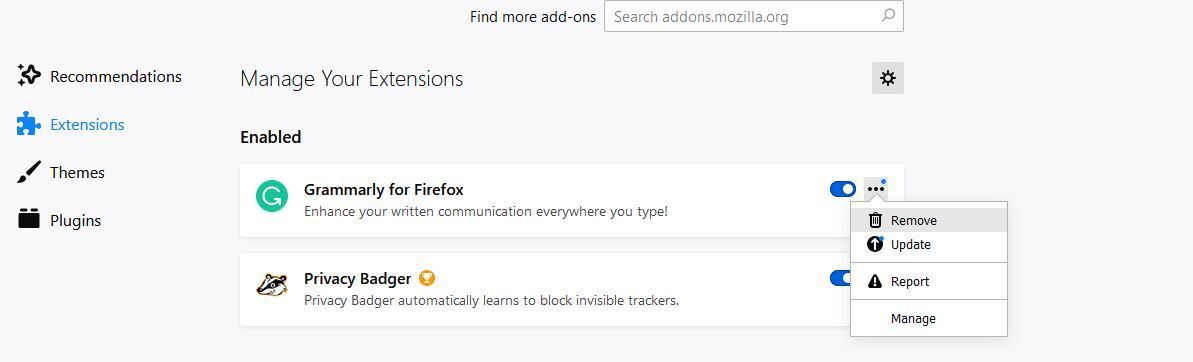

Firefox

There’s a dearth of publicly available statistics about how many extensions Firefox has, but back in late 2017 a blog post from Mozilla, the nonprofit in charge of Firefox, said there were more than 6,000 of them. It’s unlikely that Firefox has come close to catching up to Chrome (and Edge) in the intervening three years.

But the extension ecosystem shouldn’t be judged on sheer numbers. It’s quality that counts. And based on that, Firefox stacks up well to the Chrome extension ecosystem, even if it’s not quite as rich.

I checked many useful, well-known productivity-related extensions available for Chrome and found that almost every one of them is available on Firefox, including the organizer Todoist, Evernote web clipper, Ghostery and AdBlock ad blockers, Zoom Scheduler, Grammarly grammar checker, LastPass password manager, Airstory research and citation tool, Checker Plus for Gmail email enhancer, and the developer tool Scrum for Trello.

However, there were some good Chrome productivity extensions missing from Firefox, including DocuSign eSignature for signing contracts, invoices, and other documents, as well as the Office extension that lets you use Word, Excel, PowerPoint, OneNote, and Sway Online without having Office installed. Firefox also doesn’t have an extension for Google Drive Opener, which lets you open and create Google Docs files from within your browser.

You add Firefox extensions in much the same way you do in Chrome and Edge. Browse or search the Firefox Browser Add-Ons store, then when you’re reading a description of an extension, click the Add to Firefox button. You’ll get a notification of what permissions to your PC you need to give. Click Add, and it installs. Each is available as an icon on the upper right of Firefox. Click any extension to use it, or right-click it to change its options or uninstall it.

You can also click the hamburger menu on the top right of Firefox and select Add-ons. From here you can see all your extensions, move the slider next to any of them to disable or enable it, or click the three-dot icon to uninstall it, update it, report any issues with it, or manage its permissions.

IDG

The best browsers for extensions

Chrome and Edge have a more comprehensive extensions ecosystem than Firefox, although Firefox offers a very solid selection. In theory, some Chrome extensions might not run in Edge, although I’ve yet to come across one or hear of one that doesn’t work. So I’ll rate Chrome and Edge a tie in this category.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Syncing across multiple devices and platforms

We live in a business world in which we use multiple devices — desktop PCs and laptops running Windows and macOS, as well as smartphones and tablets running iOS and Android. We want our browser settings, favorites, passwords, and other data to be the same and sync on any device.

So I tested how well each browser synced data on two Windows PCs, a Mac, and Android and iOS devices.

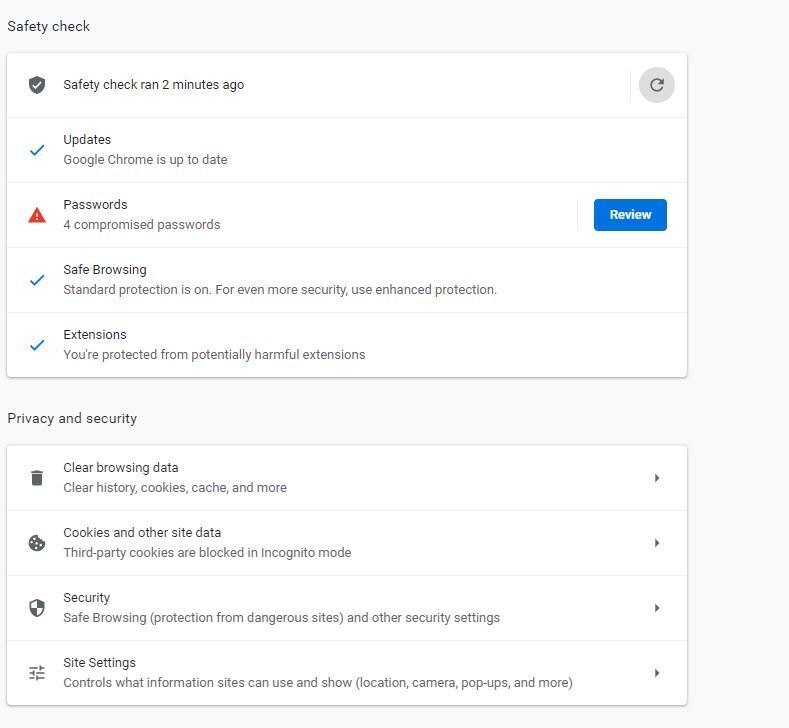

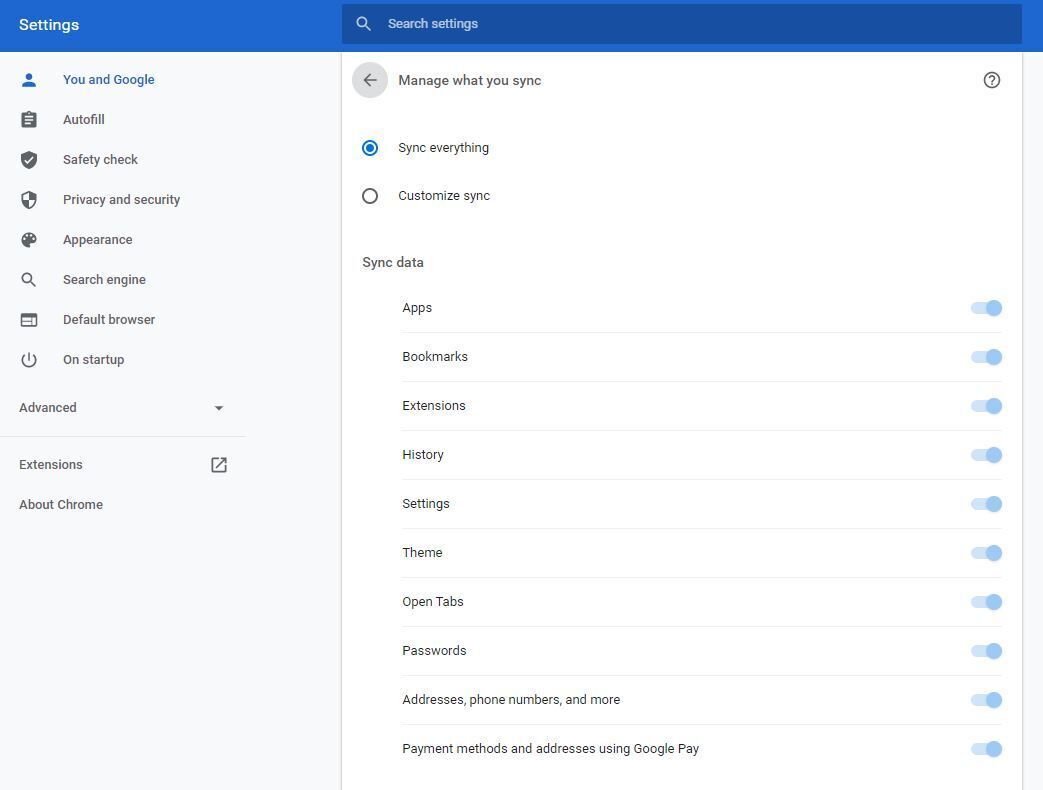

Chrome

Chrome does a superb job not just of syncing data across all of your devices, but giving you a great deal of control over what gets synced. So you can sync data on some devices and not others. And you can customize exactly what gets synced.

To do all that, you’ll need to have a Google account and sign into it on Chrome. Once you do that, click the three-dot icon at the top right of your screen and select Settings > Sync and Google services. You’ll come to the Sync and Google services page that gives you thorough control over syncing. It lets you manage what you sync, review your synced data, and encrypt your synced data.

Click Manage what you sync and you’ll come to the full list, including apps, bookmarks, extensions, history, browser settings, themes, open tabs, passwords, addresses and phone numbers and payment methods for Google Pay. To sync them all, select Sync everything. To fine-tune it, click Customize sync and move the slider to off next to what you don’t want to sync.

IDG

Back on the Sync and Google services page, click Review your synced data, and you’ll see the total number of pieces of data you’ve synced for each category — for example, 11 extensions, 489 settings, 610 passwords, and so on. However, you won’t actually see the data itself, just the totals by category. To find the data, you’ll have to spend a fair amount of time clicking around Chrome Settings, for example to count all your extensions, count all your passwords, and so on.

As for how good a job it does of syncing, there’s not much to say other than it works without a hitch. I didn’t encounter a single syncing problem. The data showed up on all devices I wanted it to and didn’t show up on devices I didn’t want it to.

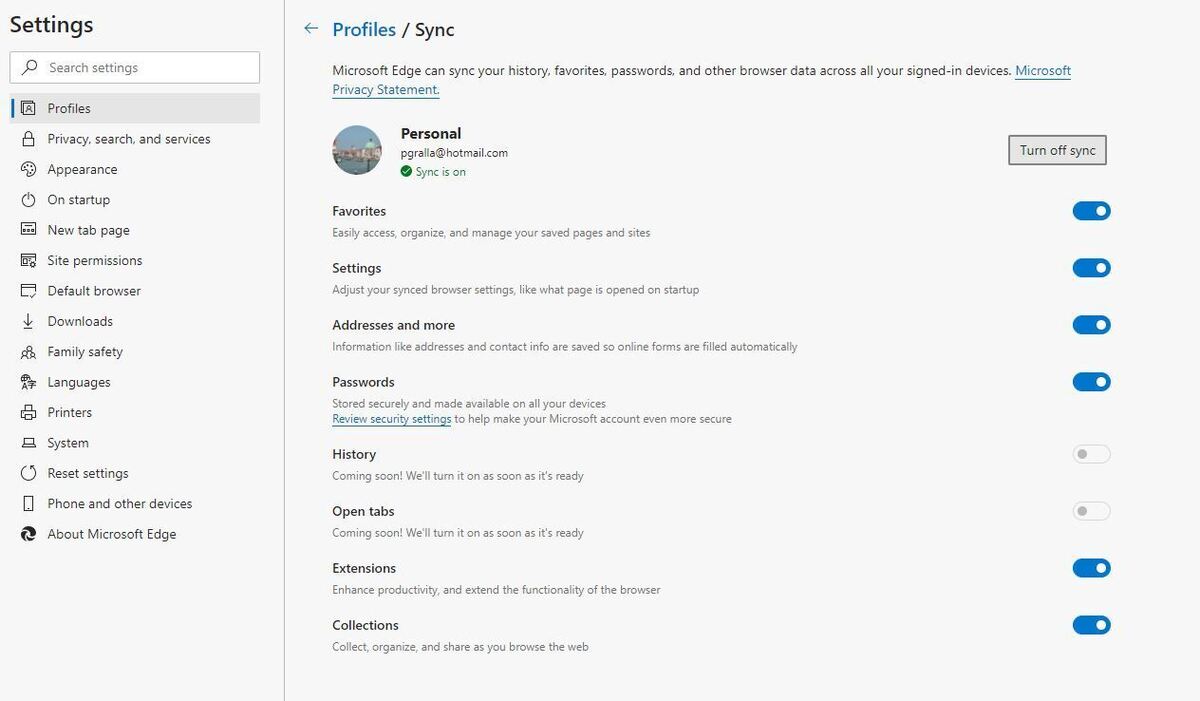

Edge

Edge doesn’t come up to Chrome’s standards when it comes to syncing data. First, the good news: It’s easy to sync data across all your devices. You’ll need a Microsoft account. Sign in, and then click the three-dot icon at the top right of Edge and select Settings > Sync. Click Turn On Sync to sync your data to other devices using Edge.

You can then choose which data to sync, including favorites, settings, addresses and contact information, passwords, extensions, and collections. (We’ll have more information about Collections in the Extras section of this article.) When you’ve made your selections, click Confirm.

Note that you can’t sync your browsing history or open tabs. Microsoft says the ability to do that is “coming soon,” but hasn’t committed to a specific date.

There are other drawbacks as well. You can’t see the amount of data being synced by category as you can with Chrome. You can’t encrypt the data being synced as Chrome does, either. Neither of these are deal-breakers. But they would be nice to have.

IDG

As with Chrome, my Edge data synced without a hitch.

Firefox

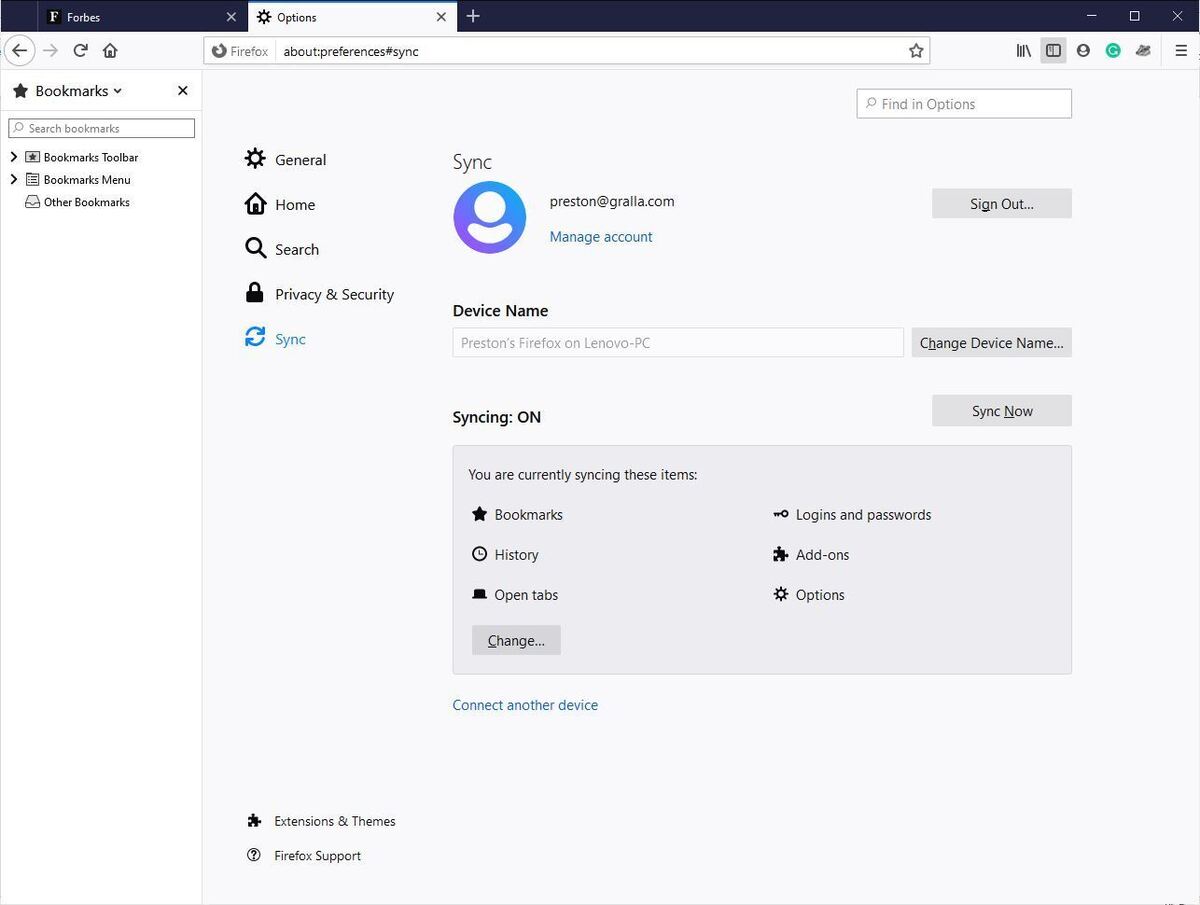

Syncing with Firefox can be a confusing experience. Sign into your Firefox account (you can create one on the same web page), and you’re automatically set up to sync. But it’s not clear how to stop syncing. There is a way to do it if you dig deeply enough, though.

First, get to sync options by clicking the hamburger menu icon on the upper-right of your screen and select Options > Sync in Windows or Preferences > Sync in macOS. In the box labeled “You are currently syncing these items,” click Change. On the screen that appears, select Disconnect. That will stop the syncing on your current device, although syncing will continue on other devices in which you’re using Firefox and have signed into your account, so you’ll have to disconnect each of those devices too. That’s a lot of work to accomplish a simple task.

IDG

Also confusing is what happens when you install Firefox on another device. When I installed it on a Mac, a tab opened up asking if I want to connect to another device. I was instructed to “Open the scanner on your Firefox app and show code when ready.” There was a “Show code” button that when clicked on showed a bar code.

But my Mac doesn’t include any kind of scanner. But what does scanning a bar code have to do with syncing my data? Nothing, apparently. I ignored the message, and then when I signed into my Firefox account, all my data synced.

You do have a choice of what data to sync. From the Sync options page, you’re shown what data you’re currently syncing. These include bookmarks, logins and passwords, history, add-ons, open tabs, and options (preferences in macOS) by default. Click Change to see everything you can sync and to turn sync on and off for different categories of data. You can sync all those, plus addresses and credit cards.

The best browser for syncing

Chrome is the winner here. It has more syncing options that either Edge or Firefox. Edge and Firefox are tied for second. Firefox lets you sync more types of data, but it can be a hot mess to use until you get used to it.

Extras

Browsers these days aren’t chock full of extra, proprietary features as they were in years past, with features like being able to mark up websites and share that with others. And that’s a good thing, because most of those extras tended to weigh down the browser, make for a confusing interface, and not add a lot of extra value.

Still, today’s browsers do have a few worthy extras. Here are the best in Chrome, Edge, and Firefox.

Chrome

Google has taken a less-is-more approach to browser design in Chrome, and likely because of that, there aren’t a surplus of notable extras in the browser. What you see is largely what you get.

That being said, there are some good extras. Foremost is the ability to do Chromecasting — “cast” whatever is on your screen to a TV or other device with a Chromecast stick attached to it. That lets you watch streaming media on your TV rather than a computer. Edge doesn’t include this same capability built into it, although you can install an add-on that will let you do the casting. In Firefox, you’ll have to try some serious workarounds that aren’t particularly simple to do, such as running an Android emulation on your PC or Mac, running Firefox inside that emulator, and then making changes to Firefox’s config file. Good luck with that.

Chrome’s password manager has one nice extra: It can generate strong passwords for you. And Chrome’s search/address bar, called Omnibox, can deliver what Google calls “rich results” that will provide answers for a search in a dropdown box rather than having to launch the search and then browse through a web page.

However, I found that feature less than compelling. Yes, it can give you sports scores (try “nba scores” or “celtics score”). And it can add numbers. But you’ll often have to use very specific syntax to find an answer to your question. For example, to find the name of a state capital — let’s say Massachusetts — you have to type “massachusetts state capital.” If you only type in “massachusetts capital,” the Omnibox will try to autocomplete the phrase rather than showing you the result.

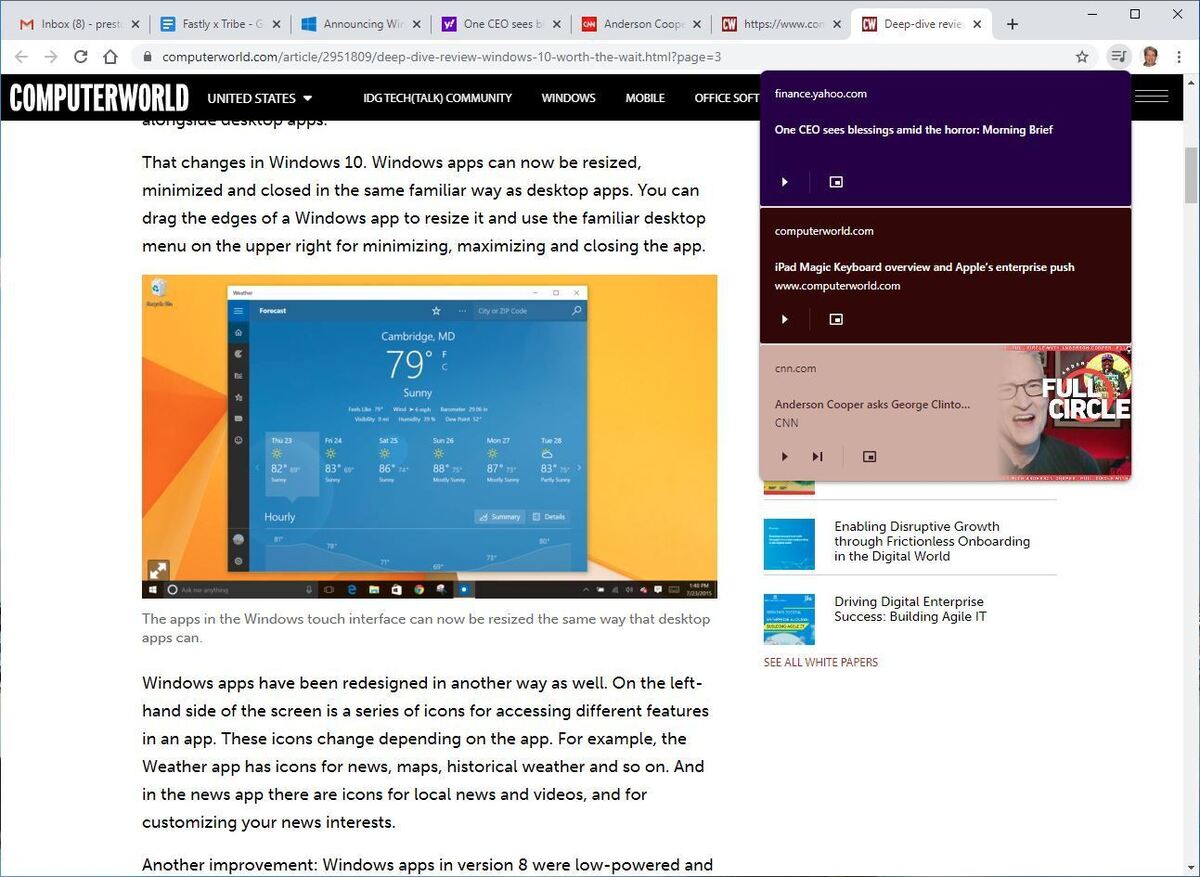

Also useful is Chrome’s built-in media player. It lets you stop and start videos and audio, jump to the next or previous track, and play the media in its own window. Especially nice is that you can control all media in all tabs simultaneously with the player. On the downside, it doesn’t let you control the volume. To get to the controller, click the small music-note icon that appears to the right of the address bar when you go to a web page and start to play music, video, or other sound.

IDG

Edge

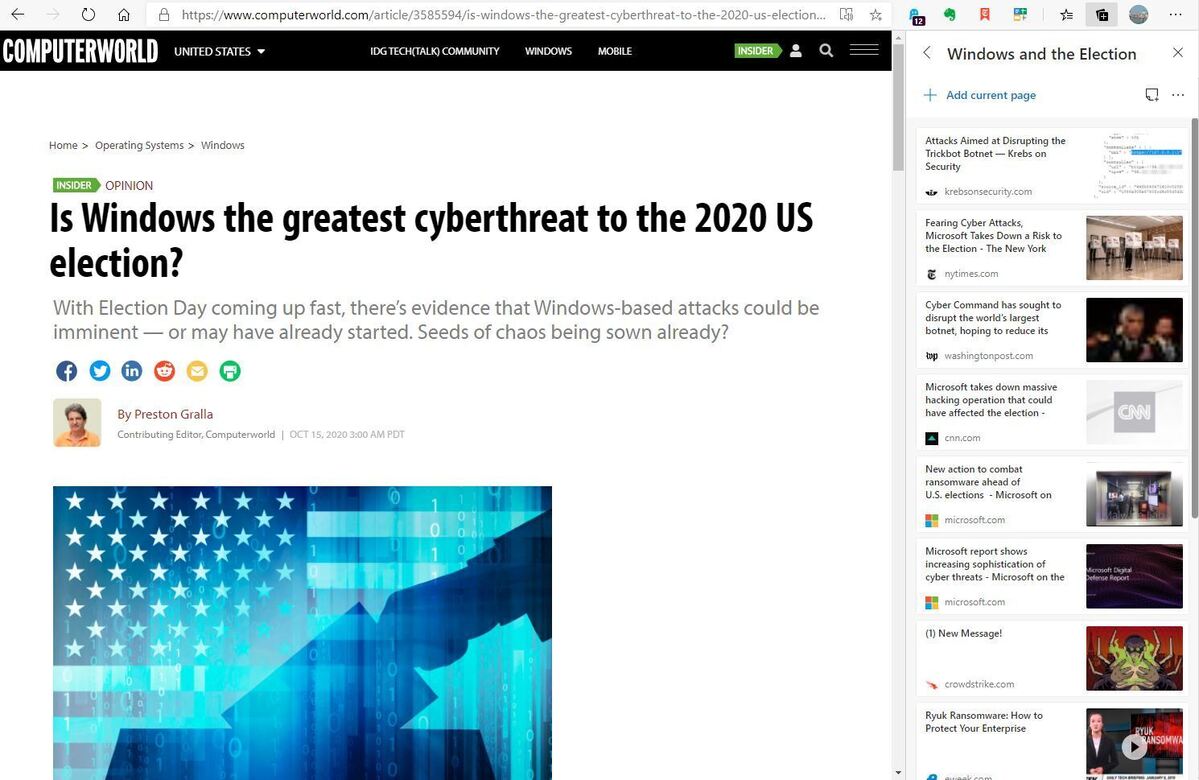

Edge has what I believe to be the best single feature offered in a browser: Collections. It lets you gather web pages, images and portions of web pages into a sidebar and organize them by categories. You can also add notes to each of your collections and send them to Excel, OneNote, Word, or Pinterest. I’ve found it to be an incredible productivity-booster, and I use it constantly throughout my working day.

To use it, click the Collections icon, a + sign inside what appear to be folders or documents, at the top right of the screen. The Collections pane opens on the right as a sidebar. The first time you use Collections, it will automatically start a new collection for you. Select “New collection” at the top of the pane and type in a name. On return visits, click the + Start new collection link and type in its name.

To add the web page you’re on to the collection, click Add Current Page. You can drag images to the collection to add them, as well as selecting text or sections of web pages and dragging them to the collection. If you have multiple collections, you can drag images or selections to any collection in the main Collections list.

IDG

To add a note, click the note icon in any collection. You can change the text formatting of any note, as well as add images to it.

You can also add web pages to a collection without actually opening the Collections pane — just right-click on a neutral area of the page and in the pop-up menu that appears, select Add Page to Collections and choose the collection you want to add it to or start a new one. You can add images and selected text to a collection using the right-click menu as well.

How might you use Collections? In just about any way possible. You can set up different collections for each of your projects and store web-based research there. You can set up collections for your budgets, for marketing research, for just about anything to do with your work.

You can also easily delete collections so that you don’t get overwhelmed by your research. It’s so easy to create collections you’ll probably find yourself creating them even just for a day or two for short-term research and then deleting them.

Firefox

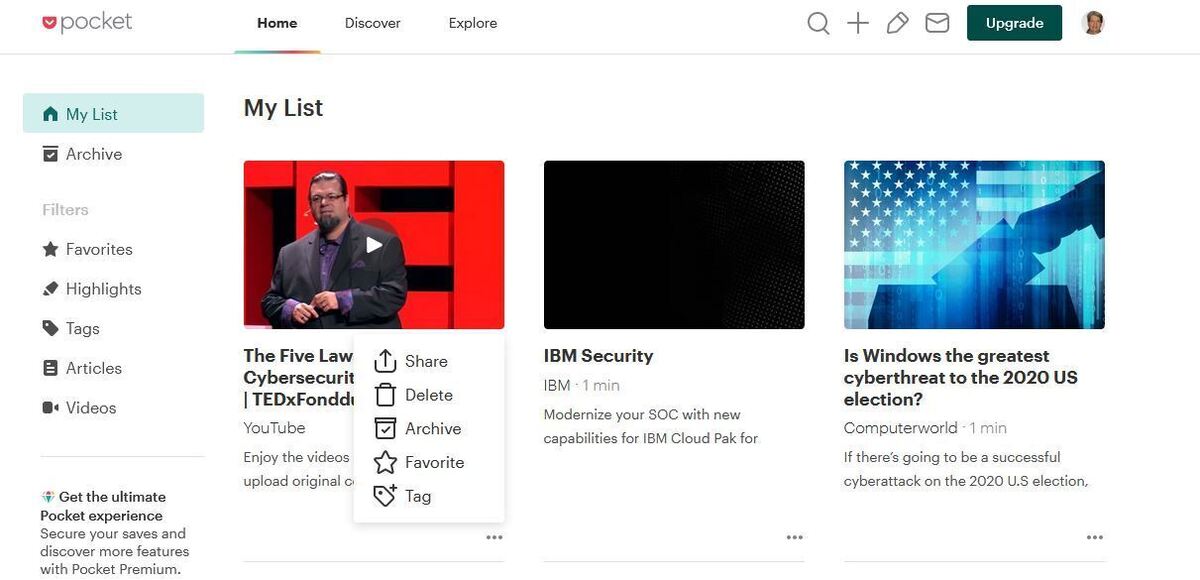

The most notable built-in extra in Firefox is Pocket, which lets you save web pages, articles, and videos so you can review them later. To use it, click the small Pocket icon just to the left of the bookmarks icon in the address bar. If you don’t yet have a Pocket account, you’ll be able to sign up for one. Once you have an account, click the Save to Pocket icon (a shield) whenever you’re on a web page you want to save. You can also send a URL via email to have a page added to Pocket.

IDG

To view items you’ve saved to Pocket, click the hamburger menu icon at the top right of the screen and select Library > View Pocket List. Your Pocket List opens in a new tab.

You can add tags to any item you save to make it easier to organize things. You can search across everything you’ve saved, mark some as favorites, highlight some, and so on. You can archive items so they show up only when you look through your archives. Because all this is available on mobile devices as well as desktops and laptops, all the information is with you wherever you go.

I didn’t find Pocket as useful as Collections. It’s a little more awkward to use, and unlike Collections, your Pocket content isn’t visible in a sidebar, so you can’t view it while you’re web browsing. You can pin your Pocket List tab so it’s always available among your tabs, but that still requires an additional click and takes your focus away from the content you’re viewing. That additional step may be enough to put you off using it. And although you can use tags as a way to organize your content, doing that can be time-consuming and require you to redo tags if you decide to reorganize things. The organization of Collections is much more straightforward.

The best browser for extras

If you use the web for research, you’ll find Collections in Edge the best extra you get in the three browsers. Although Firefox’s Pocket tool is useful, because of its design, you may not use it as much as Edge’s more straightforward Collections feature. As for Chrome, Chromecasting is the most important extra you’ll really care about — and it’s available in Edge via an add-on, so Edge is the clear winner here.

Enterprise features

In businesses, a browser isn’t a standalone piece of software. It’s an essential part of any company’s suite of productivity tools. So in this section we look at the things IT needs to know about each browser, including deployment, management, links to other productivity software, and more.

Chrome

Chrome relies, to some extent, on enterprises using tools from companies other than Google (notably Microsoft) for deployment and management. Google does, however, have its own tools as well. These are the most important kinds of tools businesses can use to manage Chrome:

- Microsoft Group Policy. This is for businesses that use Group Policy as their primary method of managing their applications. You use group policy to manage Chrome as you would any other application.

- Chrome Browser Cloud Management. This free tool lets IT enroll and manage Chrome across Windows, macOS, and Linux using the same Google Admin console as G Suite/Google Workspace and Chrome OS management. It offers information for troubleshooting and insights about how Chrome is used, with details such as device types, OS version, browser version, installed extensions and policies applied per browser. Go here to get details and to use it.

- Third-party management tools. These include Intune from Microsoft, as well as VMware Workspace One and Jamf.

With all these tools, enterprises can control permissions for browser use, such as for installing extensions. They can be based on, for example, on identity and organization units, as well as applied on a site-by-site basis. The tools also allow for the creation of block lists and allow lists for sites, apps, and content types.

Enterprises can use their normal software distribution tool for creating browser images to deploy across the enterprise. Google has an MSI available at chrome.com/enterprise. As for browser updates, Google recommends that enterprises keep Chrome’s auto update turned on so that it happens automatically, although it can also be managed via the tools mentioned above.

There’s also some integration between Chrome and G Suite/Google Workspace, notably allowing employees to search through their company’s Drive folders from the Chrome search box.

Edge

Microsoft offers a wealth of tools for deploying, managing and controlling browser use, far more than can be covered here. For a start, there’s Microsoft Group Policy and Intune. But that’s just the beginning. Office 365 customers can use Microsoft Endpoint Manager, which can configure more than 250 policies. FastTrack offers remote deployment guidance, compatibility assistance, configuration advice, and more. There are also plenty of self-guided videos for helping with deployment and configuration on Microsoft Mechanics on YouTube.

For controlling permissions for Edge, including extension use, enterprises can use Azure Active Directory and Azure AD Conditional Access. That includes not just blocking extensions, but also installing extensions automatically enterprise-wide and making sure they can’t be uninstalled. For details, see this document.

There are also many security tools for Edge for enterprises, including Microsoft Security Baselines in the Microsoft Security Compliance Toolkit. Microsoft also has a wide variety of tools for deploying Edge and then configuring or restricting updates using Microsoft Edge Update policies.

There are quite a few links between Edge and Office 365/Microsoft 365, including using Edge and Microsoft’s search engine Bing to do enterprise-wide searches. Edge can also be configured to show you all the Office files you’ve been recently using when you open a new tab. It can also recommend files you might want to open, based on your recent usage. See more details about using Edge and Bing in concert with Office 365/Microsoft 365 in enterprises.

Those are just the highlights. There’s plenty more as well.

Firefox

Firefox relies on two Microsoft tools for managing enterprise Windows browser use: Group Policy and Intune. For macOS it uses Configuration Profiles. For Linux, it uses a JSON-based configuration. For installations, it provides MSIs for Windows installations and PKG files for macOS.

Firefox has more than 80 policies available for configuration. Enterprises can check out Firefox’s enterprise documentation for help, as well as its policy templates repository on GitHub.

Firefox doesn’t match either Edge or Chrome for enterprise controls. And there’s also a wild card that enterprises might consider: Firefox’s long-term financial future. If Google loses the government’s antitrust suit, the Mozilla Foundation, which develops Firefox, could have very serious money woes. Google pays Mozilla to set Google as Firefox’s default engine. Reports say the two organizations recently inked a deal for 2021 to 2023 for payments of an estimated $400 to $450 million a year, expected to be 90% of Mozilla’s revenue. The government is targeting those kinds of payments, and if it wins the suit, it may outlaw them. What might happens to Mozilla’s development of Firefox after that is unclear.

The best browser for enterprise features

Edge comes up big here. It has the most robust set of management tools for enterprises by a mile. Both Chrome and Firefox rely on some of those tools.

Chrome comes in second, because it has several tools of its own. But Firefox is a dismal third. It relies solely on third-party tools, notably Microsoft’s. And it’s not clear what will happen to the browser if the federal antitrust suit succeeds against Google.

The best browser for business

So which browser is best for your business? Chrome and Edge are faster and use fewer system resources than Firefox, are more HTML-compliant, offer cleaner interfaces and easier syncing, and have far more tools for enterprise management. Firefox does, however, offer strong privacy features — as does Edge, while Chrome trails behind.

For these reasons, Edge is the best choice for most businesses. Organizations that may have ruled out the pre-Chromium version of the browser should give the new Edge a second look. They may well be pleasantly surprised.

Edge came in either first or second in every category in our roundup and clearly offers the best enterprise tools. The browser’s tracker blocking will especially be welcomed by those who value their privacy. If you’re a Microsoft customer already using Microsoft management and deployment tools, Office 365/Microsoft 365, and/or other software, choosing Edge is a no-brainer.

However, Chrome is a better choice than Edge for some organizations. If you use G Suite/Google Workspace, you’ll want to go with Chrome, because you’ll be able to manage all your Google software from a common console.

This article originally appeared on ComputerWorld.