Cloud uptime is critical today, but vendor-provided data can be confusing. Here’s an analysis of how AWS, Google Cloud and Microsoft Azure compare.

The cloud is not just important; it’s mission-critical for many companies. More and more IT and business leaders I talk to look at public cloud as a core component of their digital transformation strategies — using it as part of their hybrid cloud or public cloud implementation.

That raises the bar on cloud reliability, as a cloud outage means important services are not available to the business. If this is a business-critical service, the company may not be able to operate while that key service is offline.

Because of the growing importance of the cloud, it’s critical that buyers have visibility into the reliability number for the cloud providers. The challenge is the cloud providers don’t disclose the disruptions in a consistent manner. In fact, some are confusing to the point where it’s difficult to glean any kind of meaningful conclusion.

Reported cloud outage times don’t always reflect actual downtime

Microsoft Azure and Google Cloud Platform (GCP) both typically provide information on date and time, but only high-level data on the services affected and sparse information on regional impact. The problem with that is it’s difficult to get a sense of overall reliability. For instance, if Azure reports a one-hour outage that impacts five services in three regions, the website might show just a single hour. In actuality, that’s 15 hours of total downtime.

Between Azure, GCP and Amazon Web Services (AWS), Azure is the most obscure, as it provides the least amount of detail. GCP does a better job of providing detailat the service level but tends to be obscure with regional information. Sometimes it’s very clear as to what services are unavailable, and other times it’s not.

AWS has the most granular reporting, as it shows every service in every region. If an incident occurs that impacts three services, all three of those services would light up red. If those were unavailable for one hour, AWS would record three hours of downtime.

Another inconsistency between the cloud providers is the amount of historical downtime data that is available. At one time, all three of the cloud vendors provided a one-year view into outages. GCP and AWS still do this, but Azure moved to only a 90-day view sometime over the past year.

Azure has significantly higher downtime than GCP and AWS

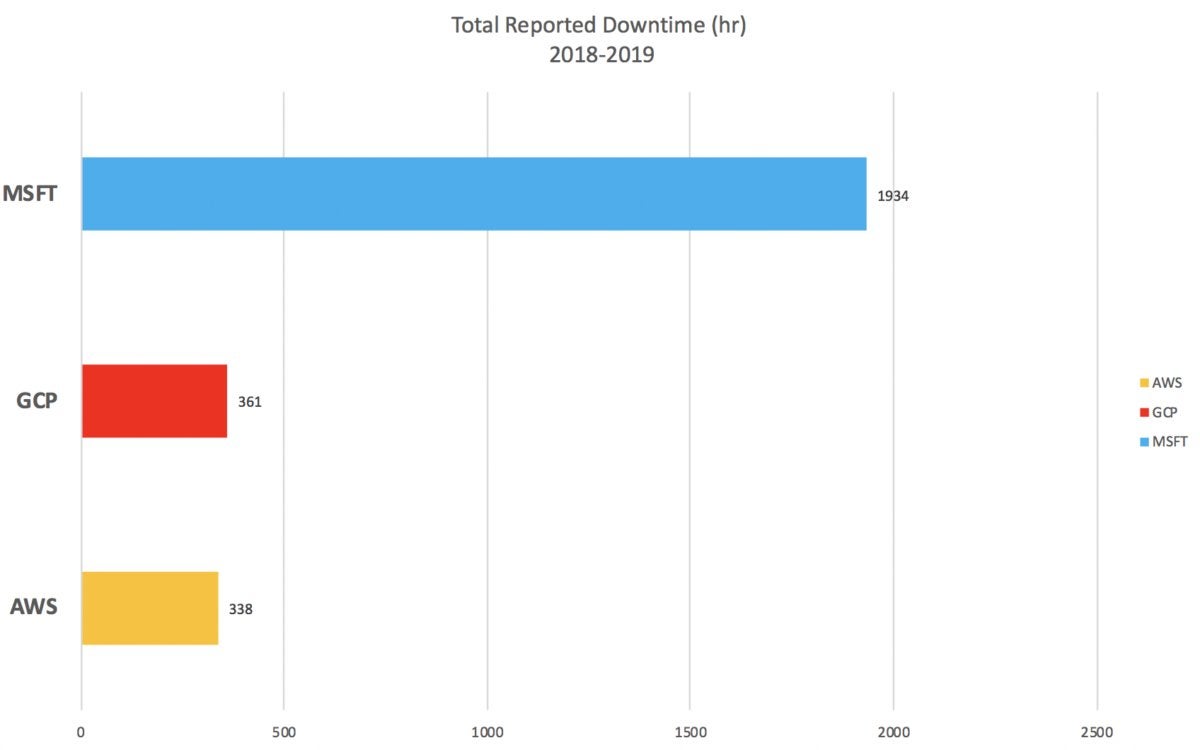

The next obvious question is who has the most downtime? To answer that, I worked with a third-party firm that has continually collected downtime information directly from the vendor websites. I have personally reviewed the information and can validate its accuracy. Based on the vendors own reported numbers, from the beginning of 2018 through May 3, 2019, AWS leads the pack with only 338 hours of downtime, followed by GCP closely at 361. Microsoft Azure has a whopping total of 1,934 hours of self-reported downtime.

Zeus Kerravala

Zeus KerravalaA few points on these numbers. First, this is an aggregation of the self-reported data from the vendors’ websites, which isn’t the “true” number, as regional information or service granularity is sometimes obscured. If a service is unavailable for an hour and it’s reported for an hour on the website but it spanned five regions, correctly five hours should have been used. But for this calculation, we used only one hour because that is what was self-reported.

Because of this, the numbers are most favorable to Microsoft because they provide the least amount of regional information. The numbers are least favorable to AWS because they provide the most granularity. Also, I believe AWS has the most services in most regions, so they have more opportunities for an outage.

We had considered normalizing the data, but that would require a significant amount of work to destruct the downtime on a per service per region basis. I may choose to do that in the future, but for now, the vendor-reported view is a good indicator of relative performance.

Another important point is that only infrastructure as a service (IaaS) services were used to calculate downtime. If Google Street View or Bing Maps went down, most businesses would not care, so it would have been unfair to roll those number in.

SLAs do not correlate to reliability

Given the importance of cloud services today, I would like to see every cloud provider post a 12-month running total of downtime somewhere on their website so customers can do an “apples to apples” comparison. This obviously isn’t the only factor used in determining which cloud provider to use, but it is one of the more critical ones.

Also, buyers should be aware that there is a big difference between service-level agreements (SLAs) and downtime. A cloud operator can promise anything they want, even provide a 100% SLA, but that just means they need to reimburse the business when a service isn’t available. Most IT leaders I have talked to say the few bucks they get back when a service is out is a mere fraction of what the outage actually cost them.

Measure twice and cut once to minimize business disruption

If you’re reading this and you’re researching cloud services, it’s important to not just make the easy decision of buying for convenience. Many companies look at Azure because Microsoft gives away Azure credits as part of the Enterprise Agreement (EA). I’ve interviewed several companies that took the path of least resistance, but they wound up disappointed with availability and then switched to AWS or GCP later, which can have a disruptive effect.

I’m certainly not saying to not buy Microsoft Azure, but it is important to do your homework to understand the historical performance of the services you’re considering in the regions you need them. The information on the vendor websites may not tell the full picture, so it’s important to do the necessary due diligence to ensure you understand what you’re buying before you buy it.

This article originally appeared on NetworkWorld.